Home as a Landscape

What would be the opposite of “home” then? Abroad? The rest of the world?

I clearly remember that, from a very young age, I felt that I needed to leave. Since my childhood I had known that I would leave my country, and would explore the wider world. It feels important to make sense of my own experience of expatriation. I left home by choice, willingly and always felt more excited than burdened by my journey.

The Freedom of Expat Life

I may be one of those who put “freedom” as an opposite for “home”, like many of the expatriates I have met through my work.

I also found that, once the excitement of life in the first two or three foreign countries calmed down, I got in touch with a profound loss: when leaving home, even by choice, we lose many links that would never be restored again. Even if we decide to go back, the world we left behind has changed, and so have we.

To make peace with this loss sometimes becomes one of the key steps in the journey of an existential migrant.

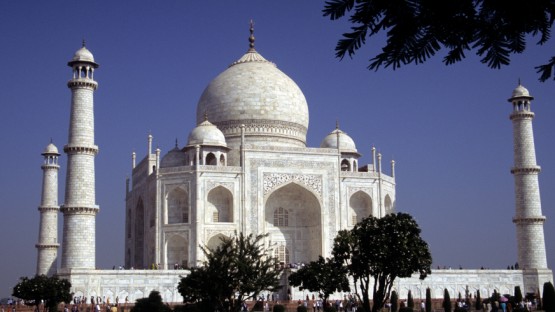

Home is also a landscape we are born into. In visual arts, for instance, any landscape needs a character, to become interesting to a human eye. You can try it yourself: draw a person on a sheet of paper, just this person and nothing else. How does it look? Suspended in the air, lost, flying? And, now try to add a horizon line, and some details of his surroundings, a tree, a dog, a house… How does it change the way you perceive this person? Does he look any different? Try to add another person, what happens then? How does the first character look now?

The more I meet expats, the more I distinguish a common theme in their stories, which actually resonate with my own nomadic journey: our weaker roots allow us to grow more self-reliant. Often the story of a voluntary migration sounds like a very solitary journey. We learn how to maintain long-distance relationships, we are able to have a romantic date through Skype or participate in a family gathering on-line.

Mobile Homes

When home becomes such a mobile concept, we become more aware of how much it depends on the people we connect with. In the end, we keep changing, as much as our geographical position. After all, home is rather a process than a fixed concept. In this constant movement, the relationships become as much “home” as the environment where we are evolving at that particular moment.

Today, with the latest developments in communication technologies, we can reach out to a friend or a parent from almost anywhere in the world. We can experience this feeling of familiarity, safety and love, or in other words the psychological comfort we usually associate with home.

It can happen, when we come back to an old home, that we experience a strong feeling of belonging. But sometimes we feel ‘nothing’ or even a deep sense of oddness. Places tend to change, especially once we have left them. They continue to evolve without us, they are indifferent to our feelings and our pains.

With people it is different. We can keep in touch and we can share how our journey is impacting us. When we do so, ‘others’ are usually able to witness our growth, if not understand it.

So, at least with people, we have a choice that we do not have with places: to bring people with us, even virtually, or to leave them behind.

Finally, no migration leaves us untouched. As much as we enjoy the excitement of our nomadic life, we nevertheless get in touch with the experience of loss that comes with it.

But making sense of all these feelings, of our relationship with home, we can reach a better self-understanding and growth.